JOURNAL, 2015

Julia Hartmann, Franziska Laue, Philipp Misselwitz

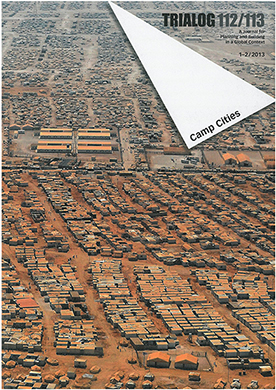

Camp Cities

Refugee camps are commonly thought of as transitory emergency situations, set up for the protection or containment of displaced victims, planned by technocrats, run by humanitarian missions, protected by the military. But the reality of camps reveals complex built environments that undergo "urbanisation processes" reminiscent of those in informal neighbourhoods and slums around the globe. Beginning as tent cities, they quickly develop differentiated quarters with local sub-identities, economic zones, markets, shops, meeting and gathering places, and forms of representation and collective action.

Camp urbanisation, however, remains a taboo and most humanitarian organisations or host governments attempt to deny or restrict it. As the civil rights of camp refugees, such as the right to employment or mobility, remain restricted, camp populations cannot become self-reliant and thus remain dependent on aid. Although exact figures on how many of the 51 million displaced people worldwide live in camps or camp-like settings are lacking, the number is significant and growing.

At the time of the writing of this editorial, the German city of Berlin has decided to house refugees and asylum seekers in newly built container camps at the periphery of the city which, conveniently, they will share with other marginalised populations such as the homeless. Thus, camp dwellers will have little or no chance to find local employment or integrate themselves into the social, cultural or economic life of the city. This out-of-sight out-of-mind strategy differs little from the way host governments with much fewer resources in Asia, Africa or the Middle East deal with their own refugee populations. Among refugee groups, in the aid community, amongst activists and an increasing number of academics, protest about camp conditions is growing. Camps, be they in Europe or the developing world, have been criticised for their resemblance to spaces of confinement and control, for their tendency to compromise civil rights, and their inability to guarantee civil dignity. In the language of social science, the establishment of camps also produces extra-territorial spaces, spaces of victimisation, spaces "outside all places" (Agier 2011) whose inhabitants are reduced to "bare life" (Agamben 1998) without access to political and legal representation.

Do we need to rethink refugee camps so as to make them places with civil dignity, or indeed abolish camps altogether? The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in the release of its new policy in 2014, seems to favour the latter, advocating for protection solutions for refugees outside of the camp system. Have camps, through their restrictions, indeed hindered refugees more than protected them? Or is this policy shift merely a recognition of the inability to serve the growing number of refugees worldwide in a time when the international community has lost interest in the plight of refugees and has radically reduced funding? As desirable as a world without refugee camps would undoubtedly be, we should not delude ourselves. Thousands of refugee camps currently exist, and many will be constructed in the future. In our world, where the number of conflicts is constantly increasing, displacement is also increasing – and with it, the need to protect and aid displaced populations. Camps are and will remain a reality. What urgently needs to be reconceptualised, however, is how camps are designed and constructed; how they connect to their social, economic and physical context; and how they evolve over time.

This TRIALOG issue calls upon architects, planners and development experts to engage with the issue of refugee camps – be it with the initial moment of emergency planning that gives "birth" to camps, with older urbanised camps, or with the discussion on the future of refugee camps within the respective host countries. A more constructive engagement could lead to a radical re-conceptualisation of what constitutes a "refugee camp": rather than being a space associated with structural discrimination, it could become a space where inhabitants can and should live with dignity. In this issue, three different moments in the development of refugee camps are looked at. Part 1 concerns the "zero hour" of camps – a phase often underestimated in its decisiveness for the future. Part 2 looks at the post-emergency phase by highlighting the visible consequences of urbanisation processes as well as the increasing contradictions and tensions between the humanitarian order and the more-local order on the ground. Part 3 speculates on the future of refugee camps. Can camps be considered long-term assets and development catalysts for the host country? Can and should camps eventually dissolve into cities?

Julia Hartmann, Franziska Laue, Philipp Misselwitz (2015) Trialog 112/113: Camp Cities. Trialog e.V., Frankfurt/Main.